The Winooski Dome: How this mill-town was almost sealed in a bubble

The concept of encapsulating a city within a giant dome sounds like something out of a science-fiction novel, or perhaps The Simpsons Movie (2007), but only 40-odd years ago this was being talked about as Winooski’s future.

As Winooski looks back at its colorful history during this year’s Centennial Celebration, perhaps the most out-of-the-box development was the consideration of the Winooski Dome Proposal Project of 1979.

In the midst of a global energy crisis, Winooski’s ingenuitous city planners applied for a $55,000 federal grant to study the possibility of constructing a dome over the city. They wanted to explore whether this design would ultimately preserve energy and save on the cost of heating.

Mark Tigan, Winooski’s Director of Community Development and Planning at the time, was a key figure in this proposal.

“[The Dome Proposal] really put Winooski on the map. We weren’t afraid to think outside of the box and use our imaginations,” he said.

Tigan said that the original idea for the dome sprang from a political maneuver to prevent the City of Burlington from creating a dam at the upper Winooski Falls. While the project would have created energy for Burlington, it also would have effectively dried up Winooski’s major asset: the Winooski River.

An energy attorney advised Tigan and his colleagues to compose a competing application for a smaller dam that would give them standing to argue against Burlington’s proposal.

“One night, after a City Council meeting, a bunch of us went out and enjoyed a glass of wine and started feeling guilty about trying to generate more energy when, in fact, we hadn't spent enough time on ways to preserve energy,” Tigan said. “So we just started brainstorming ways we might save energy and have a smaller carbon footprint, for environmental as well as economic reasons.”

In this alcohol-inspired whimsy, the idea of covering Winooski in a dome was born. According to Tigan, they initially wrote it off as ludicrous, but the next day the Community Development staff decided to investigate it closer.

After determining that the dome had the potential to reduce Winooski residents’ heating bills by up to 90 percent, they proposed the idea of a federal grant request to the City Council.

Winooski’s City Council voted, 3 to 2, to approve the application for the grant to conduct a feasibility study.

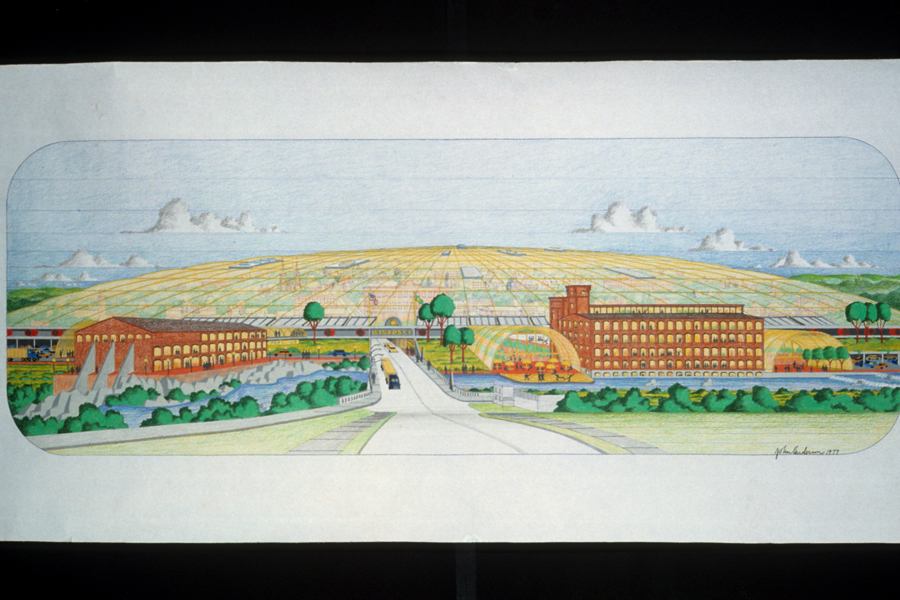

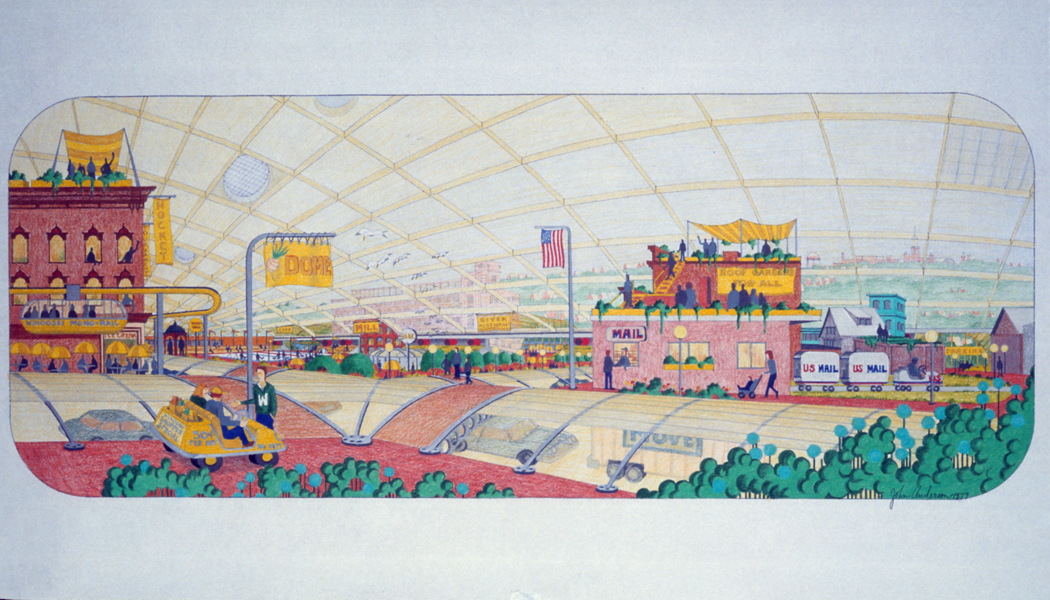

Tigan brought architect John Anderson into the fold to develop a design and visual images for the proposed dome.

Anderson had previous knowledge of dome technology from a project for a developer in Hilton Head, South Carolina in which he helped create schematic designs for a sports center using two long-span domes. In 1976, a few years before the Winooski Dome Project, he conceived the Burlington Fantasy Show in which he brought Burlington citizens’ futuristic visions (which often included large-scale domes) to life through his illustrations.

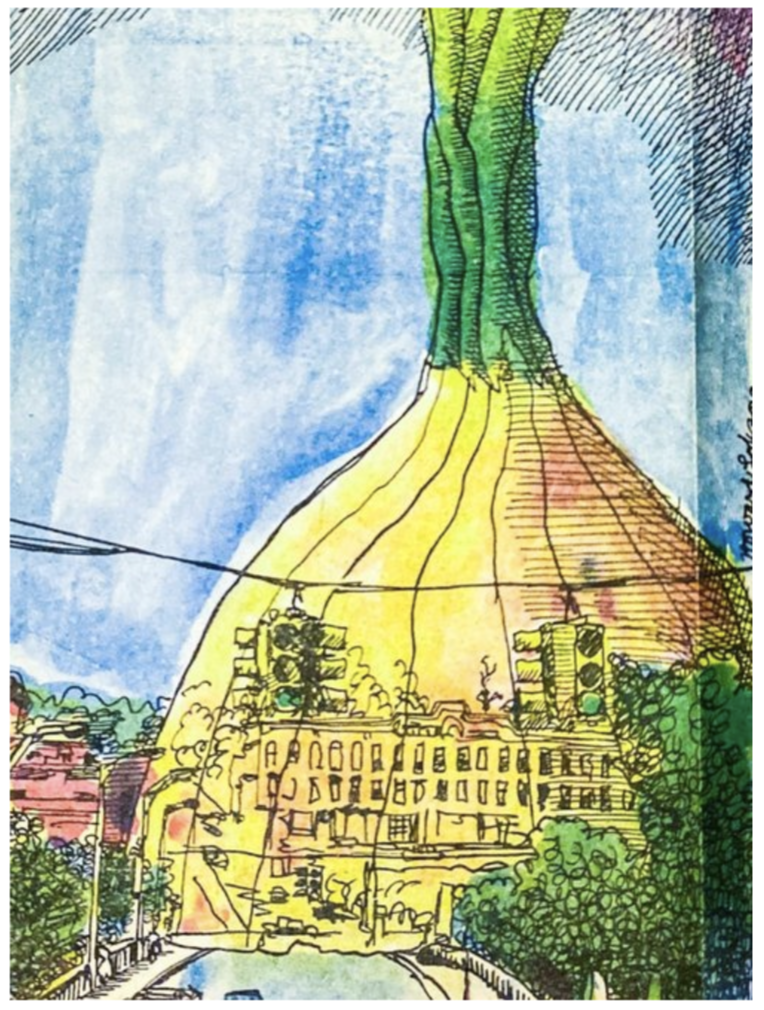

Anderson devised a dome design for Winooski that was relatively flat; he described it as a hairnet of steel cables, shrouded in a transparent or opaque vinyl material.

“We would raise the air pressure inside the dome, just over normal atmospheric pressure. This extra pressure holds its shape, and it would essentially inflate like a balloon,” he said.

According to Anderson, if the fabric was ever punctured, the dome would deflate very slowly over a long period of time.

Using colored pencil on paper, Anderson created two four-foot-long drawings of the projected dome. One offered a perspective of the exterior from the vantage point of Colchester Avenue, while the other allowed the viewer to imagine the inside of the dome and what life would look like underneath it.

“They asked me to do these drawings so that there would be a big visual that they could use to get people interested in the whole concept,” he said. “I put a realistic vision on the idea, to continue to promote the concept and also to secure the grant money.”

The illustrations depicted underground tunnels to accommodate the flow of traffic, while pedestrians drove golfcart-like vehicles above. Today, according to Anderson, the location of the original prints is unknown.

How did the citizens of Winooski respond to the proposition of existing under a dome? According to Tigan, the public reaction was overwhelmingly positive.

“When the idea was presented to the Winooski citizens, a very, very small minority of people didn't want to do it. The majority wanted it to the extent that they created a club called the Golden Onion Dome Club,” said Tigan.

Not only could supporters proudly brandish their Dome Club Membership cards, but they could head over to the Black Rose restaurant and order a dome-bound confection called ‘Domessert.’ Some enthusiasts created T-shirts cheekily toting the phrase ‘Are You Pro-Dome or Con-Dome?’

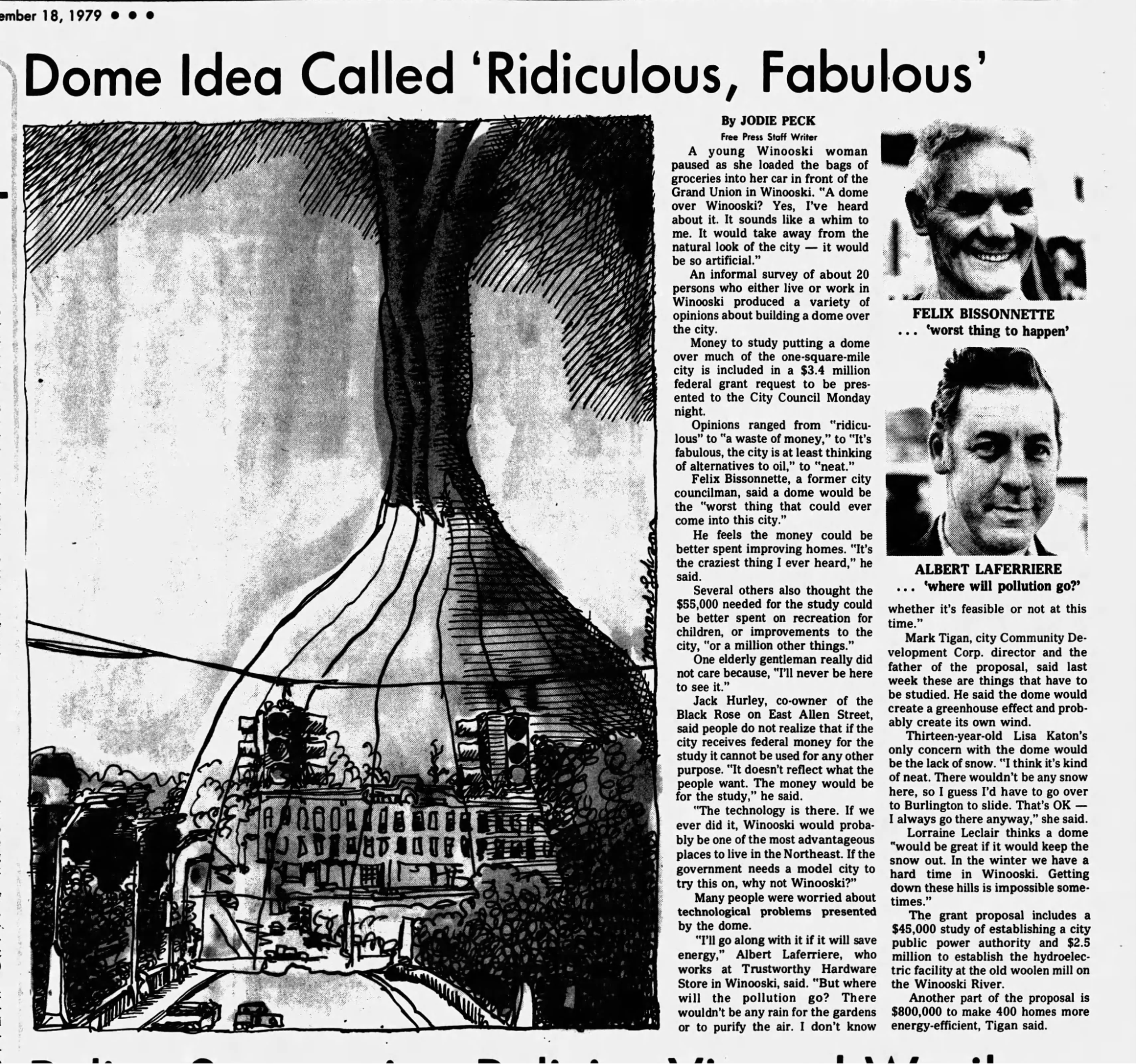

But a 1979 article by Burlington Free Press reporter Jodie Peck painted a slightly more lukewarm picture of public perception, ranging from indifferent to staunchly opposed. Some citizens were worried about how a dome would radically change their lifestyle, voicing concern about how a lack of rainfall would affect their gardens or if a dome would aesthetically obstruct their view.

“Several others also thought that the $55,000 needed for the study could be better spent on recreation for children, or improvements to the city, ‘or a million other things,’” the article cites.

Despite mixed local reception, this groundbreaking concept quickly garnered national, and then international, media attention.

“The morning after the City Council voted to approve the grant application, we had about 10 of those satellite trucks in the parking lot of City Hall,” said Tigan. “We started receiving bags of mail from grade-schoolers all over the country.”

The proposal was covered by major news outlets like the New York Times, Associated Press, and Time Magazine, as well as publications abroad, including newspapers in Saudi Arabia.

Why would Winooski, Burlington’s scrappy, mill-town sibling even be considered for federal funding, especially for such an outlandish project?

“Winooski had the second-highest federal funding per capita in the United States at the time, so we had a lot of federal funding rolling into the community. We became a kind of training ground for new federal ideas, including certain kinds of subsidized housing,” said Tigan.

The federal government continued to supply the community with funds because, according to Tigan, every time they were given money to try an idea, they were successful. This strong federal relationship brought Tigan to Washington quite a bit, where he pitched the budding dome idea to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.(HUD)

“He had been the Community Development Director in Baltimore when they were trying to preserve downtown Baltimore with a dome, and he was fascinated with the idea. He said, ‘Submit it to us and we’ll fund the feasibility study,’” Tigan recalled.

But when the Winooski Dome Proposal attracted international publicity, HUD buckled under pressure from the White House to pull back funding.

“When Jimmy Carter was president, there was the Iran-Contra crisis going on. The idea of the federal government, on Jimmy Carter's watch, giving money to a town that wanted to put a dome over it just seemed too politically incorrect, given the crisis at hand with Iran. So that money died,” Anderson said.

According to Tigan, HUD was still intent on upholding its oral commitment to Winooski to investigate the dome idea. They followed through on the promised feasibility study through a force accounting agreement, meaning that they sent U.S. government employees rather than independent contractors.

“They assigned three people from the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to come up to Winooski and do a feasibility study. One was an economist, one was an engineer, and one was a sociologist,” Tigan said.

In the report, the economist confirmed that the dome would indeed be financially feasible if home heating fuel hit $1 per gallon. The engineer said it was feasible to cover the whole city in a dome, but recommended restricting it to a smaller area such as the downtown. The sociologist was not as enthusiastic as the economist and engineer, deeming it impractical to change the fabric of the community so drastically.

“I would say that the sociologist was wrong. He made certain assumptions about the people of Winooski, like that they love cold weather and snow. In other words, he didn't spend much time on the ground for his research,” said Tigan, remarking that he had never met a Winooskian who enjoyed shoveling snow.

This report was presented at the First (and only) International Dome Symposium that was hosted by St. Michael’s College on the outskirts of Winooski from March 26-27, 1980. The event consisted of speeches, presentations, and a trade show where architects who built domes over sports facilities and even a small community in Antarctica could display their products.

The famous architect R. Buckminster Fuller, then 85, flew to Winooski from Brazil to make the keynote speech. Fuller was a prolific futurist who had invented the geodesic dome, and he was ecstatic about the prospect of a dome encompassing the city.

“The [Winooski] community is talking about going into environment controlling in a major way, for the whole community,” Fuller said at the symposium. “It is a very daring scheme, although the idea has been in the wind and we have talked about it in other ways. I’m going to show you some other projects that have been carried on, but the basic question is: ‘Are we being practical?’”

Though the TVA engineer had regarded the construction of a dome over Winooski as feasible back in 1979, current UVM professor and engineer Eric Hernandez is dubious of the project’s attainability.

Hernandez is an associate professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and was named UVM’s 1st Sweeney Green and Gold Professor of Civil Engineering in 2018. He specializes in structural engineering, and he had some thoughts about the practicality of a city-wide dome.

“First you have to think about the term ‘feasible’: Feasible essentially means that it doesn’t violate the laws of physics,” Hernandez said. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that the technology at the time is available to actually do it in a reliable or economically viable way.”

Hernandez said that although technically the laws of physics would not prevent the development of a dome, there are many different factors that would play into the ultimate decision to produce one.

“The problem with this idea is that it works in a perfect world, but when we take it to the real world engineers have to begin to think about what could go wrong. What happens if something fails? It doesn’t really survive that kind of analysis,” he said.

In the event of a natural disaster, Hernandez was skeptical about the resiliency of a flexible dome: Would it be able to endure extreme weather?

“As engineers, we take all the precautions and we think about all the possible things that could go wrong. We try to design against each one of those but it's inevitable that at some point in time, some sort of imponderable thing could happen, and the system might fail,” he said. “And then if it fails, you have to think about how you are going to recover from the failure.”

Hernandez does not foresee the dome concept making a comeback in the engineering community, at least to the scale of a city, anytime soon.

“It is an impractical idea, in my opinion. I would think there is a very small probability that somebody would take the responsibility to design this dome today. There are so many ways in which this thing could fail,” said Hernandez. “And how long would a dome over the city last, how would we repair it? After 5 years, can we go about 500 feet in the air to patch these holes? It would just be a nightmare to actually make this practical.”

Current Winooski City Council member Thomas Renner, who was elected in early March of this year, said he finds a lot of humor in the consideration of a modern Winooski Dome Proposal. But if the idea of pursuing federal grant money to study the feasibility of a dome was presented to the City Council today, he said he would probably vote against it considering that it might not be the most prudent use of city funds.

“I would first like to hear the guidance of staff who would have put foresight and research into it, and I’d take that into advisement along with what people in the city were saying,” Renner said. “But my gut feeling is that there’s probably many other grants we could apply for that can better the city before we try to build a dome again.”

In terms of the reaction of today’s Winooskians, Renner said he thinks history would repeat itself in the excitement over the dome concept’s lighthearted absurdity.

“I think they would embrace the fun of it, maybe Four Quarters would come out with a dome beer or something,” Renner said. “However, I don’t think anyone would want their tax dollars going toward actually building it.”

In light of Winooski’s celebration of 100 years of cityhood, Tigan reflected on the tremendous spin-off benefits felt by the Dome Proposal.

“We got interest from developers for the mills, and all the renovations that have happened since, that might not have otherwise happened without the international attention from the dome,” he said.

Though the Winooski Dome Project never came to fruition, the memory of this chapter of the city’s history stands as a testament to the innovative minds at Winooski’s helm.

“It’s a call to younger generations to think big and think out of the box,” Tigan said.

Watch Mark Tigan and John Anderson speak about their experiences pioneering the Winooski Dome idea here.